Writer: Tiffany Whisner, Coles Marketing

It’s a week-long camp giving visually-impaired students an experience that’s truly “out of this world.” Since it began in 1989, Space Camp for Interested Visually-Impaired Students (SCIVIS) has offered kids with special visual needs the chance to do everything Space Camp® has to offer — from learning how the space shuttle works to taking part in a real-life mission simulation.

But SCIVIS has something else other camps don’t. It lets students with visual impairments learn and have fun just being themselves with others who are just like them.

What may be a small step for others — is a huge step for them.

25 years of space

SCIVIS takes place at the U.S. Space & Rocket Center in Huntsville, Ala. It’s coordinated by teachers of visually-impaired students and is composed of four separate programs: Space Camp; Space Academy; Advanced Academy Focus on Space Travel; and Aviation Challenge.

It’s also completely accessible — computers used by the students are adapted for speech and large-print output, and materials and equipment used during the mission simulations are available in Braille and large print.

It’s also completely accessible — computers used by the students are adapted for speech and large-print output, and materials and equipment used during the mission simulations are available in Braille and large print.

SCIVIS Program Coordinator Dan Oates has a creed the camp follows. “At our beginning, many were given little chance but due to the people in our lives, we find ourselves in a wonderful place with wonderful people. Let us flourish in our learning, find joy in our experiences and remember our friends and knowledge we gained at Space Camp.”

And this year, SCIVIS celebrated its 25th anniversary. Twenty-five years of creating an intangible feeling that comes with visually-impaired students enjoying themselves, making peer group connections and learning about the mystery and adventure of space.

But SCIVIS didn’t make it through a quarter-century without bumping into some moon rocks along the way.

The launch of an idea

Space Camp® launched in 1982 as the brainchild of rocket scientist, Dr. Wernher von Braun. Then director of the NASA Marshall Space Flight Center, von Braun believed there should be a place for young people to experience the excitement of space. Under the guidance of Edward Buckbee, the first director of the U.S. Space & Rocket Center, Space Camp was born.

“In 1989, a woman inquired about the space programs available for adults, but when she told them she was blind, they apologized but said she couldn’t participate,” Oates said.

Believing Space Camp is run by NASA, the woman penned a letter to her congressman, complaining NASA had refused her access to their facility, and as a U.S. government agency, it was against the law. Her congressman forwarded the letter to Buckbee, who wanted to find a way to make the Space Camp experience one for people of all ages — and all abilities.

So he called back to his hometown of Romney, W.Va., where the West Virginia Schools for the Deaf and Blind were located. Could a space program be accessible? Could it be adapted to suit the needs of visually-impaired students? Superintendent Max Carpenter believed it could.

So he called back to his hometown of Romney, W.Va., where the West Virginia Schools for the Deaf and Blind were located. Could a space program be accessible? Could it be adapted to suit the needs of visually-impaired students? Superintendent Max Carpenter believed it could.

And so did Dan Oates, who was at the time working at the Schools for the Deaf and Blind.

But Oates’ placement at the school and belief in the dream that would become SCIVIS came as the result of quite an interesting journey.

Each star has a different fate

“I grew up in Romney,” Oates said. “It’s a very small community, and the West Virginia Schools for the Deaf and Blind are a big part of that community. My mother and uncle both worked there, and so I was always very connected to it.”

Even so, in his younger days, Oates had the wrong perception of the school and its students. He didn’t think it was in his future to have any association with the school. He called it “the ignorance of my youth.”

Oates went to Fairmont State University in West Virginia and earned his Bachelor of Science in recreation management, securing a successful job and comfortable life. But due to federal funding issues, that job ended — leaving Oates looking for something he could do to help pay the bills in the meantime. He found himself using his recreation skills to demonstrate chair caning — a weaving method — as part of a job teaching local crafts classes.

“At the time, I didn’t think I should be teaching a crafts class,” Oates said. “I didn’t think I should be sharing an office with a 74-year-old, teaching a class to people about how to cane chairs.”

Then, one day, Oates got an interesting call. The person on the line asked Oates if he thought he could teach a blind student how to cane a chair. It was the West Virginia Schools for the Deaf and Blind.

“Chair caning — it was a vocation the school wanted to keep alive, as an industry for blind people to get involved in and become employed. And they wanted to know if I could teach blind students how to cane chairs. I knew I could.” It’s interesting how things come together in the right place at the right time.

“As I started my work at the school, I got very much wrapped up into teaching and learning what makes the kids tick,” Oates said. It was originally only a three-month position, but Oates admitted he was enjoying the job more than he thought he would. Ralph Brewer was the principal of the school at the time.

“Ralph was my mentor. He saw something in me I didn’t even realize was there. He saw the work I was doing with the students and encouraged me to pursue it.”

The school offered to pay for Oates to get his master’s degree. He received his Master of Education from the University of Pittsburgh, with teacher certifications in blindness and low vision; orientation and mobility; and low-vision therapy.

“I never really got it before,” Oates said. “I didn’t understand how shortsighted I was being. But there was something else at work — Ralph got me to Pitt and then back to Romney for a career. I have been blessed to find myself in the career I was really meant for.”

And it has made all the difference. Oates is now retired from the West Virginia Schools for the Deaf and Blind after 30 years. He spent 14 years as an orientation and mobility instructor and 16 years as an outreach specialist, managing a program for West Virginia families with blind babies.

“It has given me a real sense of purpose,” Oates said. “I can think back on all the families I’ve helped, and a lot of the students are now friends. Working with them has broadened me as an individual. It’s been amazing and has changed my life.”

The stars align for SCIVIS

All the stars aligned when fellow Romney resident Edward Buckbee was looking for a way to make Space Camp accessible to the blind. When Buckbee contacted the West Virginia Schools for the Deaf and Blind about creating a space program for the visually impaired, Oates wanted to help.

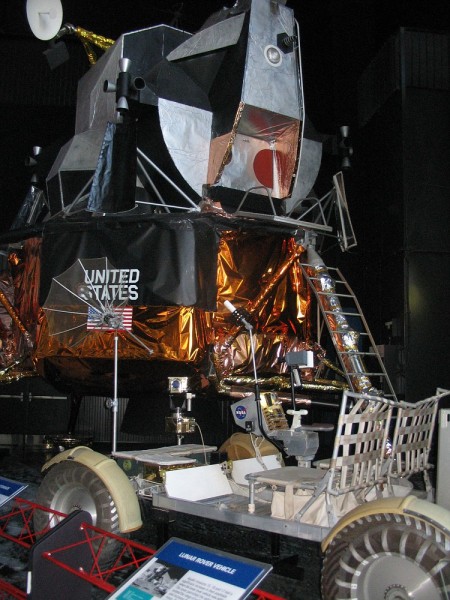

The Space Camp home base was in Huntsville, Ala. That’s where Buckbee was working at the U.S. Space & Rocket Center, and it made sense to start SCIVIS there. Plus, they could use the facilities and materials from Space Camp, an unparalleled environment with historic space, aviation and defense hardware.

The Space Camp home base was in Huntsville, Ala. That’s where Buckbee was working at the U.S. Space & Rocket Center, and it made sense to start SCIVIS there. Plus, they could use the facilities and materials from Space Camp, an unparalleled environment with historic space, aviation and defense hardware.

For the first 15 years or so, all the kids attending SCIVIS were from the West Virginia Schools for the Deaf and Blind. But one day in 2006, that all changed.

“John Thompson, the executive director of the Lighthouse for the Blind in St. Louis, contacted me to learn more about SCIVIS,” Oates said. “He was very interested in creating some experiences for the students of Missouri through the Lighthouse.”

Originally known as Industrial Aid for the Blind, Inc., the Lighthouse had heard of SCIVIS through word of mouth and saw promise in the program. That year, Thompson sent a handful of kids to try out what has turned into an annual program running the last full week of September. Today the Lighthouse is sending nearly 40 kids to take part in SCIVIS each year.

And just this year, another shooting star appeared. As part of its “See the Future” program, the Lighthouse wanted to reinvest into programs for the blind and donated $50,000 to the U.S. Space & Rocket Center Foundation, which manages the scholarship programs to students for space camp.

With that donation, Oates was tasked with developing SCIVIS on an international level, adding culture, diversity and a greater reach. He reached out to organizations working with visually-impaired people, parent associations for the blind and foundations for the blind.

“John (Thompson) realized those kids probably weren’t going to get to travel the world,” Oates said. “He wanted to enrich their lives by bringing the culture of students from other states and countries to them.”

In this year’s SCIVIS program, there were more than 200 students involved — from 24 states and 11 countries.

Mis sion control, do you read me?

sion control, do you read me?

“The most important component, other than the students, is the chaperones,” Oates said. “They have to find the kids who are interested, make sure they are ready to go and prepare them for the adventure. They serve as advisors to the SCIVIS staff.”

All the chaperones are teachers in the fields of visual impairment, orientation mobility, Braille transcription or teachers from schools for the blind. They act as technical support for any vision issues.

But the “crew trainers,” as they are called, are in charge of the space program experience. They are young people who have completed at least two years of college and have had extensive training in how to work with visually-impaired kids and the space program.

“Every team is made up of 12 to 16 kids, and each team has a crew trainer,” Oates said. “He or she is responsible for their week and molding them into a team.”

Each child must be independent and able to take care of their daily needs as well as have a basic understanding of English. They must be comfortable with being away from home, since the overnight camp is a week.

“The program is geared toward astronaut training, with a number of simulators like what an astronaut would train on,” Oates said. “There are capsule and shuttle simulators, mission control room and space stations.”

What is a typical day at SCIVIS like? The students start with breakfast, and then they may head to a briefing to hear how the space shuttle works. Then, it’s time for mission training — where each student is given a specific role for a simulated mission, whether commander of the space shuttle, station scientist or the flight director at mission control.

What is a typical day at SCIVIS like? The students start with breakfast, and then they may head to a briefing to hear how the space shuttle works. Then, it’s time for mission training — where each student is given a specific role for a simulated mission, whether commander of the space shuttle, station scientist or the flight director at mission control.

After that, it’s off to a simulator experience where they can learn the feeling of an atmosphere with no gravity. Then it’s lunch and time for the actual mission, where they assume the role they learned earlier that morning. Oh, and how about an IMAX movie and a tour of the rocket park?

And it’s all accessible — made especially for those kids with vision impairments. There are adaptations everywhere. Braille and large-print materials are available, and there is a vast array of magnification devices. The computers in mission control have speech and screen enlargement software, and there are accessibility features in whatever media is being used.

“The kids are surprised by the accessibility,” Oates said. “It’s not something they are used to seeing. They walk into this public place, and someone hands them everything in Braille. Twenty-five years ago when we started this program, we provided all the materials ourselves. But as a huge credit to Space Camp, when they did a technology upgrade in 2006, they got with the accessibility manufacturers and made sure with the software upgrade there would be total accessibility for the SCIVIS attendees.”

“You can see them change,” Oates said. “The biggest comment I hear from the kids is it’s a week when they don’t have to explain themselves to anyone, and they can relax and be with friends.”

Each student graduates at the end of the week, with new skills, new friends and a new sense of confidence.

“I feel bad taking the credit,” Oates said. “It’s the staff and the chaperones who are the magic. They are who changes their lives.”

SCIVIS is a program that grew mostly by word of mouth from just a handful of students to hundreds. And 25 years later, it’s that program that is giving visually-impaired students the self-confidence to reach for the stars.

SCIVIS is a program that grew mostly by word of mouth from just a handful of students to hundreds. And 25 years later, it’s that program that is giving visually-impaired students the self-confidence to reach for the stars.

“Time flies when you’re having fun. I can’t believe it’s been 25 years,” Oates said. “Every year we learn even more, more to improve on for the next year. Everyone should have the ability to be comfortable where they live, work and play, whether they have a disability or not. But it takes the commitment of organizations like Space Camp that believe in the importance of accessibility and continue to push for it.”

Thank you for sharing this!