Writer: Tiffany Whisner, Coles Marketing

Have you ever had a conversation with a friend or family member and just can’t seem to communicate to them what you’re thinking? Communication problems can be the result of anything from hard-to-decipher nonverbal cues or too little information to the wrong communication method or not paying attention.

Many relationship problems — whether in your personal or professional life — stem from poor communication.

But how is that challenge compounded when you speak English, and the person you are communicating with — uses sign language?

Hearing tools for the future

Jordan Stemper was born and raised near Milwaukee, Wis. And at 11 years old, he received a cochlear implant.

“In high school, I was mainstreamed with no interpreter,” Stemper said. “It was a personal choice of mine.”

According to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), about two to three out of every 1,000 children in the United States are born with a detectable level of hearing loss in one or both ears. And one in eight people in the U.S. — more than 30 million people — aged 12 years or older have hearing loss in both ears.

According to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), about two to three out of every 1,000 children in the United States are born with a detectable level of hearing loss in one or both ears. And one in eight people in the U.S. — more than 30 million people — aged 12 years or older have hearing loss in both ears.

Many people with hearing loss can benefit from hearing aids, assistive technology devices and cochlear implants as well as from captioning and American Sign Language (ASL).

“One of the main impacts of hearing loss is on the individual’s ability to communicate with others,” notes the World Health Organization. “However, when opportunities are provided for people with hearing loss to communicate, they can participate on an equal basis with others. The communication may be through spoken/written language or through sign language.” Stemper’s eyes were opened to the magnitude of this particular communication barrier when he attended Rochester Institute of Technology for his undergraduate studies.

“For college, I decided to attend Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) because of the school’s excellent design programs and wonderful accessibility services for the Deaf,” he said. Indeed that is the case. The National Technical Institute for the Deaf is one of the nine colleges at Rochester, providing deaf and hard-of-hearing students with state-of-the-art technical and professional education programs, complemented by a strong arts and sciences curriculum, to prepare them to live and work in the mainstream of a rapidly-changing global community and enhance their lifelong learning.

Stemper originally studied graphic design but, when he lost his motivation for that field, switched to industrial design.

“I’m so glad I did that because I’m always the one to notice design flaws in products,” he said. “I wanted to help solve those design problems and make better, more intuitive products.” During his time at RIT, he met and befriended many deaf individuals.

“I use sign language just as much as I use spoken English,” Stemper said. “Being able to speak English and hear, I often helped interpret for my Deaf peers. It also opened my eyes to this big problem — communication barriers.”

That helped inspire him to found a brand-new venture called MotionSavvy.

That helped inspire him to found a brand-new venture called MotionSavvy.

Putting things in motion

“Being an industrial designer, I was always looking for ways to improve the design of different products and services,” Stemper said. “I also have very creative friends who just happen to be interested in the same things I am. In 2012, there was a contest called the Next Big Idea, which was hosted by ZVRS, a video relay service for the Deaf. It was a contest about how to improve accessibility for Deaf individuals.”

The competition encouraged students to create a product, technology or business that would benefit the deaf and hard-of-hearing community. The teams had to be made up of three to five members, with at least three different majors represented.

“I got my friends together — Wade Kellard and Ryan Hait-Campbell — and we began brainstorming,” Stemper said. “We went through many pages of ideas, designs, problems and solutions. Then we saw a video of the Leap Motion device, and everything just clicked.”

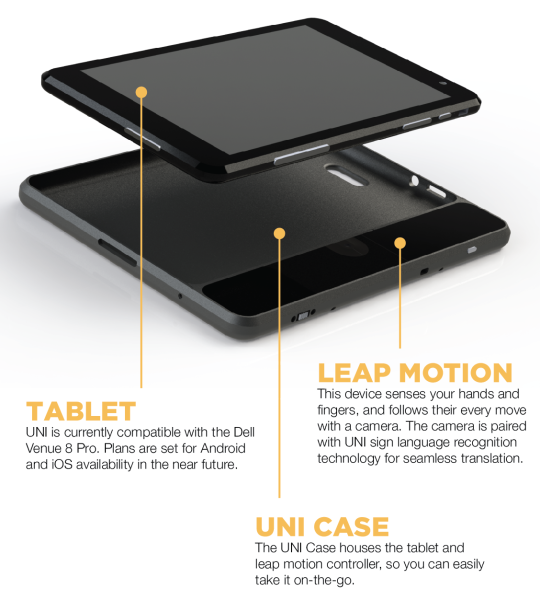

The Leap Motion Controller senses how you naturally move your hands, and it lets you use your computer in a whole new way. You can point, wave, reach and grab. You can pick up something and move it.

According to its website, the Leap technology tracks all 10 fingers up to 1/100th of a millimeter. It has a 150-degree field of view and a Z-axis for depth. That means you can move your hands in 3D, just like in real life. Plus, it can track your movements at a rate of more than 200 frames per second. That’s how the action on the screen keeps up with your every move.

What if Stemper and his teammates could incorporate ASL with the Leap technology? What if they could translate ASL to spoken English? Or what if they could educate others on how to sign ASL?

The possibilities seemed endless. And as luck would have it, during the competition the trio was approached by Alexandr Opalka, a software engineer.

The possibilities seemed endless. And as luck would have it, during the competition the trio was approached by Alexandr Opalka, a software engineer.

“He said he had heard about us and our idea and was working on that same idea,” Stemper said. “We were ecstatic because none of us are software engineers. So we teamed up, and MotionSavvy was born.”

MotionSavvy won third place and $2,000 in the Next Big Idea competition. It was just the start the team needed.

A revolutionary new device

Stemper is the chief design officer of MotionSavvy. His job is to oversee all design aspects of the company. Hait-Campbell is the chief executive officer; Kellard is the chief strategic officer; and Opalka is the chief technology officer.

The MotionSavvy team has since expanded — with eight total team members including a database engineer, ASL consultant, financial specialist and media coordinator.

“All of us are Deaf, and we have experienced communication barriers growing up,” Stemper said. “Also, we have seen our friends and peers struggle to find jobs because of the lack of communication.”

Working with the Leap Motion technology, MotionSavvy came up with the idea for UNI — a two-way communication system that uses gesture recognition technology to translate ASL into spoken English and spoken English to text.

Working with the Leap Motion technology, MotionSavvy came up with the idea for UNI — a two-way communication system that uses gesture recognition technology to translate ASL into spoken English and spoken English to text.

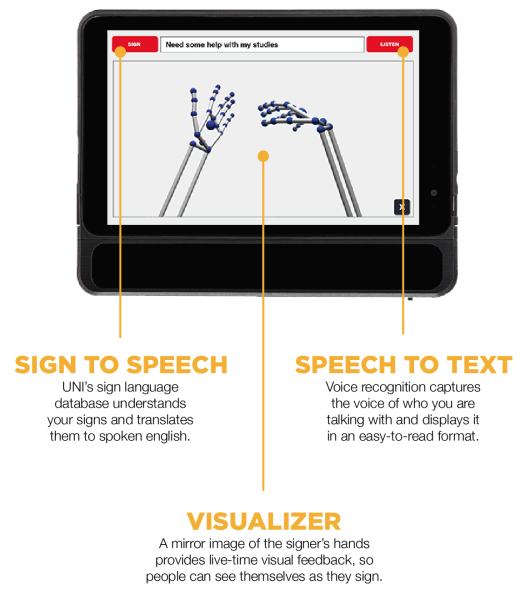

It’s the first-of-its-kind, portable device that translates sign language into audio and spoken word to text, finally empowering the deaf and hard-of-hearing to lead full lives and have boundless careers. The Leap Motion device senses your hands and fingers, and it follows their every move with a camera. The camera is paired with UNI sign language recognition technology for seamless translation.

“The Deaf person will sign above the UNI device. UNI will recognize what was signed, then translate what was just signed to spoken English,” Stemper said. “The hearing person hears what UNI says, and then responds back. UNI uses voice recognition software to process what is being said and will display it as text for the Deaf person to read.”

UNI’s sign language database understands your signs and translates them to spoken English. A mirror image of the signer’s hands provides live-time visual feedback, so people can see themselves as they sign. And voice recognition captures the voice of who you are talking with and displays it in an easy-to-read format.

Stemper and the MotionSavvy team hope UNI will help those who are deaf or hard-of-hearing have more opportunities to pursue a career, connect with friends, excel in school and bond with their family.

“Ever since we have started promoting what we’ve been doing with UNI, there has been tremendous positive feedback from the community,” he said. “Everyone is very excited to see this succeed.”

The price of success

But success doesn’t come without obstacles and bumps in the road along the way. Stemper said the biggest challenge so far has been trying to make the UNI device affordable for deaf individuals.

According to the World Health Organization, adults with hearing loss have a much higher unemployment rate. And among those who are employed, a higher percentage of people with hearing loss are in the lower grades of employment compared with the general workforce.

According to the World Health Organization, adults with hearing loss have a much higher unemployment rate. And among those who are employed, a higher percentage of people with hearing loss are in the lower grades of employment compared with the general workforce.

“Most Deaf individuals in general do not have high incomes, due to difficulty obtaining jobs, and it’s been a challenge for us to figure out what is the best way to make this affordable for all,” he said.

And just like any other language, ASL is a language of its own and has its own accents and variables.

“We have taken that into account, and we have developed a program called the Sign Builder,” Stemper said. “It is a personalization feature for individuals to be able to program their own unique sign or their own variation of the sign. To use it, you apply the English label and record the gesture. Then it will be stored in the dictionary for later use.”

Every time a person signs, UNI remembers the movements and improves its translation. UNI also gets smarter as you use it, and it can be trained to understand your own personal signing style.

“We began working on the UNI nine months ago,” Stemper said. “It’s been amazing to see how far we have come in just nine months, and we are very excited to keep this ball rolling and see where it goes. We are grateful for the support we have received, and that really helps us keep working at full steam ahead.”

Breaking communication barriers

UNI is currently compatible with the Dell Venue 8 Pro, and plans are set for Android and iOS availability in the future. What does Stemper think are the next steps for the UNI?

UNI is currently compatible with the Dell Venue 8 Pro, and plans are set for Android and iOS availability in the future. What does Stemper think are the next steps for the UNI?

“Once we have ASL to English translation, our goal is to incorporate other spoken languages and other signed languages in UNI. Then, other countries can use this wonderful device, and Deaf individuals can travel to other countries and still be able to communicate with others.”

And vital to their success is their current Indiegogo campaign. On this international crowdfunding site, MotionSavvy is promoting pre-orders for UNI and campaigning for contributions.

“This is basically our market validation,” Stemper said. “If people pre-order this, then we know we have a product people will buy. Without these pre-orders, we don’t have a product. It’s important to us so we can prove to ourselves, our investors and to the general public that communication between Deaf and hearing individuals is still a challenge, and UNI is one of the ways to solve that problem.”

The campaign started on Oct. 21 and will close on Dec. 20, with a goal of raising $40,000. At last check, there were more than 200 funders.

In order to communicate with hearing peers, deaf individuals currently have to use lip reading, pen and paper and texting. The aim is for UNI to change all that.

“The Deaf community is very proud of their heritage, culture and the use of ASL,” Stemper said. “They don’t see being Deaf as a problem; it’s just who they are. They can still do anything but hear. But we hope UNI will be important to them because it allows them to express their feelings and thoughts through ASL, which is their primary means of communication.”

Just last week, the UNI was named one of “The 25 Best Inventions of 2014” by TIME. And it’s not just for the deaf or hard-of-hearing. Hearing people can use UNI as well to talk to their deaf friends, family or co-workers.

Just last week, the UNI was named one of “The 25 Best Inventions of 2014” by TIME. And it’s not just for the deaf or hard-of-hearing. Hearing people can use UNI as well to talk to their deaf friends, family or co-workers.

“The sky is the limit,” Stemper said. “Back in the day, the technology we are working on was only dreamed of. I never believed it could actually happen, and now here we are, making it happen. I believe the design and development of assistive technology will always be on the rise. Technology is there to assist us in our everyday lives, and it always will be.”