There are many assistive technologies available today to help people who have some sort of speech impairment, known collectively as the Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) field. Usually these communications involve some type of computer-generated sp eech, or recordings of common sayings performed by an actor.

eech, or recordings of common sayings performed by an actor.

Voice banking is one option that lets those who can no longer speak effectively to continue communicating using their own natural voice.

This is done by having the person record a list of words and phrases while they still have the ability to do so. As the name implies, this “bank” of spoken words is then used to generate language using a speech generation device (SGD), such as a computer or tablet.

If the bank is large and varied enough, it can create a virtually infinite combination of words and sentences.

Obviously, the drawback of voice banking is the user must still have the ability to record clear speech. So, the candidate is typically someone who has been diagnosed with a condition that is known to lead to loss of speech, such as motor neuron disease (MND), and have the time and wherewithal to make recordings while they still are able.

But the benefit is equally obvious: to allow the person to continue to communicate verbally in perpetuity using their own voice.

But the benefit is equally obvious: to allow the person to continue to communicate verbally in perpetuity using their own voice.

“For a person who is losing their voice, having their own voice in their speech generation device would perhaps encourage them to use it more than some sterile packaged voice,” said Craig Burns, an Assistive Technology Specialist with Easterseals Crossroads with 21 years of experience in AAC.

And as with many things, technological advancement is making the process more accessible and cheaper. Voice banking used to be cost-prohibitive for most people, according to Burns. “With the recent web-based options, I believe it will become more mainstream.” he said.

Making bank “deposits”

Generally, creating a voice bank takes a minimum of six to eight hours to record over a period of time, usually weeks or months, and involves producing around 1,600 or more sentences. This process can take longer if the candidate needs to take lots of breaks.

The speech recorded must be fully intelligible and clear — what you “deposit” in the voice bank is exactly what you will get out. Luckily, withdrawals are unlimited!

The speech recorded must be fully intelligible and clear — what you “deposit” in the voice bank is exactly what you will get out. Luckily, withdrawals are unlimited!

Voice banking is different from “digital legacy” services, which are used to record important messages for posterity.

One of the challenges in voice banking is the best time to do it is while speech is not yet fully impacted. The candidate may have just received their diagnosis of whatever condition is affecting their speech, and may not yet have come to terms with the possibility they may lose their voice. So awareness and education are key.

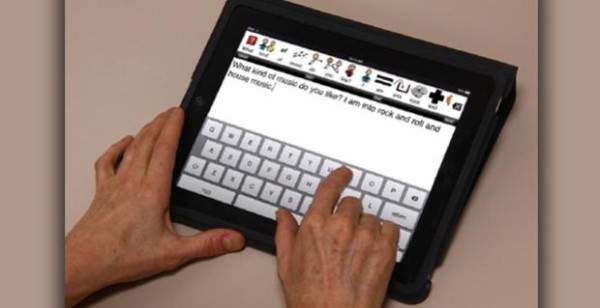

There are two versions of voice banking: digitized speech and synthesized speech. Digitized speech involves directly recording anticipated phrases, names, etc. and recording each one: “How are you,” “I want to go to the store,” etc. Usually these common phrases are then placed on a computer as a sound file, which the user can access using a touch screen.

Synthesized speech involves creating a computer file of all the sounds a voice makes using the alphabet and combinations of letters, which are then combined to create words. This method is obviously more complex, but gives a greater amount of versatility and a larger potential bank of speech that can be produced.

Synthesized speech involves creating a computer file of all the sounds a voice makes using the alphabet and combinations of letters, which are then combined to create words. This method is obviously more complex, but gives a greater amount of versatility and a larger potential bank of speech that can be produced.

Much of the recording can even be done by the user on their own, according to Burns. “The person recording a voice should have a microphone that is of higher quality than most people have as well as a place to record that has very little, if any, background noise.”

ModelTalker and more

One of the major versions of voice banking software available today is ModelTalker, developed by Dr. Tim Bunnell, Director of the Nemours Center for Pediatric Auditory and Speech Sciences.

(Bunnell was a guest on the ATU podcast in 2014; click here to hear his interview.)

He became interested in speech perception as a graduate student, which eventually segued into finding better ways to synthesize speech.

Voice banking “is an ideal technology for people who, for instance, have been diagnosed with a disease like ALS where they know there’s a very good likelihood that they’ll lose the ability to speak, but they are still able to speak fluently at the time of diagnosis,” Bunnell said during the podcast.

Voice banking “is an ideal technology for people who, for instance, have been diagnosed with a disease like ALS where they know there’s a very good likelihood that they’ll lose the ability to speak, but they are still able to speak fluently at the time of diagnosis,” Bunnell said during the podcast.

Unlike digitized speech that can only play back words or phrases that have been directly recorded, synthesized speech platforms like ModelTalker allow more communication freedom than ever.

“What we’re able to do is take those recorded phrases and actually convert them into a synthetic voice that still sounds like the person who recorded the speech originally, but is able to say anything, including things that the person didn’t originally record,” he said.

One thing Bunnell and others encounter in voice banking is the user’s desire to record their voice in a very animated way, with lots of changes in intonation and tone.

One thing Bunnell and others encounter in voice banking is the user’s desire to record their voice in a very animated way, with lots of changes in intonation and tone.

“Actually, that’s counterproductive when you’re trying to build a synthetic voice. Because in order to be able to find the bits and pieces to paste together smoothly, you want a fair amount of uniformity in the recordings. So, it’s actually better for people not to be very expressive in the way they do the recording,” he said.

Researchers are working on ways to make voice banking faster and easier, so the recording time could be as little as 30 minutes in the future.

Voice donors

Even when it’s not possible for a person with speech impairment to record his or her own voice for banking, another option is the use of voice donors. This could be a loved one or friend whose voice is employed so there is still a level of familiarity and comfort with the speech used.

ModelTalker also encourages people to become voice donors for strangers, much like blood donation. Craig Burns sees opportunities for using voice donors to customize speech generating devices to their own tastes, as well as help differentiate between them so everyone using a SGD does not sound alike.

“I see young AAC users choosing voices not typically found in current speech generating devices to help personalize their devices, especially when there may be a group of AAC users together,” he said.

Another exciting area of application is children who experience speech impairment at a young age. Rather than having to spend a lifetime using generic-sounding AAC, they could pick and choose their own voice — now, and in the future.

Another exciting area of application is children who experience speech impairment at a young age. Rather than having to spend a lifetime using generic-sounding AAC, they could pick and choose their own voice — now, and in the future.

“It would be useful for children to be able to select or change voices as they grow. If there was a voice for a six-year-old girl, speech therapists could download that voice for the child’s device,” Burns said. “As the child grows, the therapist or family could download an older child’s voice. In effect, the device speech output could change as the individual matures physically in age.”