When Richard Propes was born with spina bifida in 1965, doctors predicted he wouldn’t live more than three days in the hospital, and they even advised his parents to withhold treatment. Fortunately they refused. This month, he celebrated turning 58 — less than a decade older than the Spina Bifida Association, which is celebrating its 50th anniversary this year.

October is a meaningful time for Propes, as it not only marks his birthday and Spina Bifida Awareness Month but also National Disability Employment Awareness Month (NDEAM). He has a long history of helping fellow Hoosiers with disabilities and currently serves as the Director of Provider Services for the Bureau of Disabilities Services.

It’s fitting for Propes to look back with surprise and pride because he’s seen more than he ever expected, not only in his personal and professional life but in how Indiana — and the world — has changed vastly in its treatment of spina bifida and people with disabilities in general.

From Dire Days to Decades of Support

Literally meaning “split spine,” spina bifida occurs when a baby’s neural tube fails to develop or close properly, typically within their mother’s first 28 days of pregnancy. As the Spina Bifida Association states on its website, it is “the most common permanently disabling birth defect,” affecting approximately 166,000 people in the United States. Common conditions associated with it include limited mobility, bladder and bowel dysfunction, and learning disabilities.

Propes was born during an era in which little was known about spina bifida and the outcome was bleak. When fellow Hoosier John Mellencamp was born with the defect in the decade prior, most babies died from it. In fact, the year he was born, he was the first of only three babies at Riley Hospital for Children to undergo a pioneering form of corrective surgery. (One of the newborns died during the operation while the other lived until just 14.)

“1965 was still a time when the vast majority of babies born with spina bifida died or were expected to experience lifelong challenges such as hydrocephalus (water on the brain) or cognitive disability, and were considered unlikely to ever be independent in any way,” Propes said. “The mid-’60s were a time when the medical knowledge of spina bifida was growing. For example, the shunt to treat hydrocephalus was just invented in the mid-’50s. So, I was born with all the usual pessimistic expectations of spina bifida but also on the edge of technological advancements that would increase the likelihood of survival over time.”

Propes is anything but a pessimist. To give you an idea of his lighthearted attitude and dark humor surrounding his circumstances, he requested his surgeons to play the fittingly titled and then popular song “Footloose” before his first below-knee amputation in 1985. (To his surprise and delight, they blasted it in the operating room.) He became a double below-knee amputee and wheelchair user the next year, but that only propelled him further into public service.

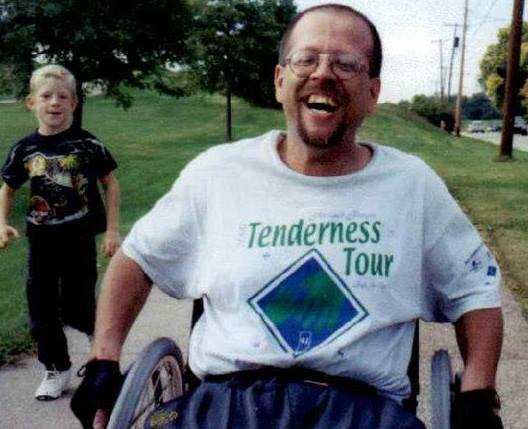

In 1989, Propes started the Tenderness Tour. Traveling across Indiana completely by wheelchair, he embarked on this mission to raise awareness of child abuse and collect donations for children’s organizations around the world. He continued this effort for the next 34 years, traveling more than 6,000 miles and raising roughly one million dollars.

As he said in a previous interview, “When I returned home from that first Tenderness Tour, I couldn’t deny that I had far more potential than I could have ever imagined. I mean, seriously, if I could travel alone around Indiana for 41 days and 1,000 miles, what couldn’t I do? I’ve been wheeling and working ever since.”

Giving Back Through Employment

Propes’ first job after graduating college was for downtown Indy’s Winona Memorial Hospital.

“At that time, the idea of employment for those of us with significant disabilities was still a bit foreign,” he said. “So, I definitely had a learning curve about life skills, being work ready and balancing performance with self-care. But the staff members at Winona were amazing and very patient.”

Little did Propes know this job would carve out his career path.

“When I worked at Winona, I was the admission coordinator for the behavioral health unit and worked crisis intervention in the ER,” he said. “We served people with disabilities a lot, and I began to realize how underserved people with disabilities were because mental health was often dismissed. I became known for actively seeking out serving people with disabilities because I ‘get it.’ I understand disability, daily challenges, institutionalized ableism and so much more. I was able to support people in finding their own tools for healing. That ER work directly led to my eventual role with my current agency, the Bureau of Disabilities Services. Service coordinators within the agency were familiar with my work and jumped at the chance to hire me when I became available. Now, I get to impact things on a system-wide level and that’s exciting.”

Throughout his career working for the state of Indiana, Propes has helped countless children and adults achieve their highest potential by connecting them with the right providers of residential and support services to meet their needs. And he credits Indiana for making it possible for him to do this work to the best of his ability.

“Indiana takes the idea of reasonable accommodation seriously,” he said. “So, if we can proactively identify things that will help me succeed, we really go for it. In fact, the ‘Reasonable Accommodation’ policies and procedures were more improved when I started my work, and my employers were very proactive about getting feedback from employees with disabilities.”

Richard Propes has come a long way, and he’s grateful for where the road has taken him.

“I guarantee you no one expected me to live alone in a house I bought or driving a car,” he said. “I think being a person with disabilities in a management role for a government agency has made me a role model for the idea that ‘you can live your good life.’”